the secret life of NaN

The floating point standard defines a special value called Not-a-Number (NaN) which is used to represent, well, values that aren’t numbers. Double precision NaNs come with a payload of 51 bits which can be used for whatever you want– one especially fun hack is using the payload to represent all other non-floating point values and their types at runtime in dynamically typed languages.

%%%%%% update (04/2019) %%%%%%

I gave a lightning talk about the secret life of NaN at !!con West 2019– it has fewer details, but more jokes; you can find a recording here.

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

the non-secret life of NaN

When I say “NaN” and also “floating point”, I specifically mean the representations defined in IEEE 754-2008, the ubiquitous floating point standard. This standard was born in 1985 (with much drama!) out of a need for a canonical representation which would allow code to be portable by quelling the anarchy induced by the menagerie of inconsistent floating point representations used by different processors.

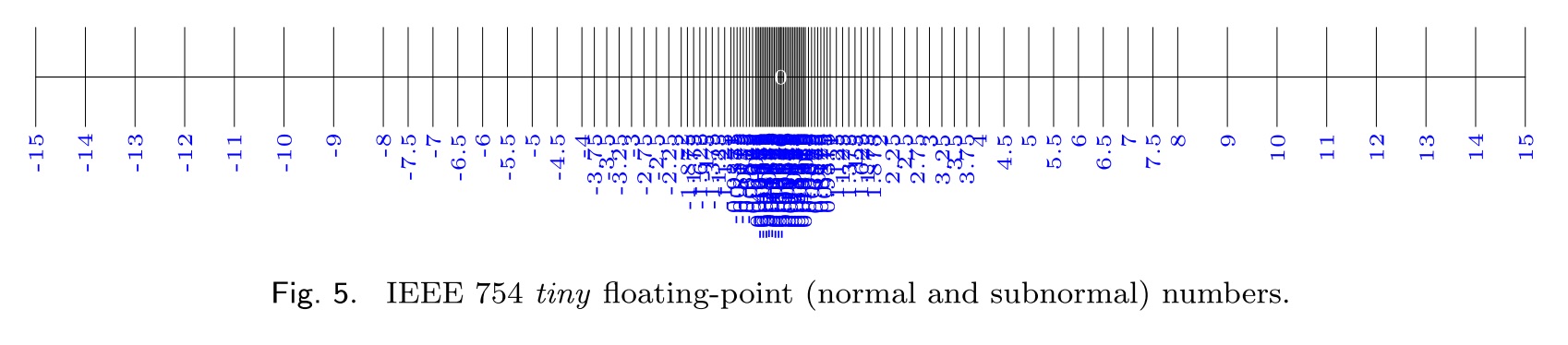

Floating point values are a discrete logarithmic-ish approximation to real numbers; below is a visualization of the points defined by a toy floating point like representation with 3 bits of exponent, 3 bits of mantissa (the image is from the paper “How do you compute the midpoint of an interval?”, which points out arithmetic artifacts that commonly show up in midpoint computations).

Since the NaN I’m talking about doesn’t exist outside of IEEE 754-2008, let’s briefly take a look at the spec.

An extremely brief overview of IEEE 754-2008

The standard defines these logarithmic-ish distributions of values with base-2 and base-10. For base-2, the standard defines representations for bit-widths for all powers of two between 16 bits wide and 256 bits wide; for base-10 it defines representations for bit-widths for all powers of two between 32 bits wide and 128 bits wide. (Well, almost. For the exact spec check out page 13 spec). These are the only standardized bitwidths, meaning, if a processor supports 32 bit floating point values, then it’s highly likely it will support it in the standard compliant representation.

Speaking of which, let’s take a look at what the standard compliant representation is. Let’s look at binary16, the base-2 16 bit wide format:

1 sign bit | 5 exponent bits | 10 mantissa bits

S E E E E E M M M M M M M M M M

I won’t explain how these are used to represent numeric values because I’ve got different fish to fry, but if you do want an explanation, I quite like these nice walkthroughs.

Briefly, though, here are some examples: the take-away is you can use these 16 bits to encode a variety of values.

0 01111 0000000000 = 1

0 00000 0000000000 = +0

1 00000 0000000000 = -0

1 01101 0101010101 = -0.333251953125

Cool, so we can represent some finite, discrete collection of real numbers. That’s what you want from your numeric representation most of the time.

More interestingly, though, the standard also defines some special values: ±infinity, and “quiet” & “signaling” NaN. ±infinity are self-explanatory overflow behaviors: in the visualization above, ±15 are the largest magnitude values which can be precisely represented, and computations with values whose magnitudes are larger than 15 may overflow to ±infinity. The spec provides guidance on when operations should return ±infinity based on different rounding modes.

What IEEE 754-2008 says about NaNs

First of all, let’s see how NaNs are represented, and then we’ll straighten out this “quiet” vs “signaling” business.

The standard reads (page 35, §6.2.1)

All binary NaN bit strings have all the bits of the biased exponent field E set to 1 (see 3.4). A quiet NaN bit string should be encoded with the first bit (d1) of the trailing significand field T being 1. A signaling NaN bit string should be encoded with the first bit of the trailing significand field being 0.

For example, in the binary16 format, NaNs are specified by the bit patterns:

s 11111 1xxxxxxxxxx = quiet (qNaN)

s 11111 0xxxxxxxxxx = signaling (sNaN) **

Notice that this is a large collection of bit patterns! Even ignoring the sign bit, there are 2^(number mantissa bits - 1) bit patterns which all encoded a NaN! We’ll refer to these leftover bits as the payload. **: a slight complication: in the sNaN case, at least one of the mantissa bits must be set; it cannot have an all zero payload because the bit pattern with a fully set exponent and fully zeroed out mantissa encodes infinity.

It seems strange to me that the bit which signifies whether or not the NaN is signaling is the top bit of the mantissa rather than the sign bit; perhaps something about how floating point pipelines are implemented makes it less natural to use the sign bit to decide whether or not to raise a signal.

Modern commodity hardware commonly uses 64 bit floats; the double-precision format has 52 bits for the mantissa, which means there are 51 bits available for the payload.

Okay, now let’s see the difference between “quiet” and “signaling” NaNs (page 34, §6.2):

Signaling NaNs afford representations for uninitialized variables and arithmetic-like enhancements (such as complex-affine infinities or extremely wide range) that are not in the scope of this standard. Quiet NaNs should, by means left to the implementer’s discretion, afford retrospective diagnostic information inherited from invalid or unavailable data and results. To facilitate propagation of diagnostic information contained in NaNs, as much of that information as possible should be preserved in NaN results of operations.

Under default exception handling, any operation signaling an invalid operation exception and for which a floating-point result is to be delivered shall deliver a quiet NaN.

So “signaling” NaNs may raise an exception; the standard is agnostic to whether floating point is implemented in hardware or software so it doesn’t really say what this exception is. In hardware this might translate to the floating point unit setting an exception flag, or for instance, the C standard defines and requires the SIGFPE signal to represent floating point computational exceptions.

So, that last quoted sentence says that an operation which receives a signaling NaN can raise the alarm, then quiet the NaN and propagate it along. Why might an operation receive a signaling NaN? Well, that’s what the first quoted sentence explains: you might want to represent uninitialized variables with a signaling NaN so that if anyone ever tries to perform an operation on that value (without having first initialized it) they will be signaled that that was likely not what they wanted to do.

Conversely, “quiet” NaNs are your garden variety NaN– qNaNs are what are produced when the result of an operation is genuinely not a number, like attempting to take the square root of a negative number. The really valuable thing to notice here is the sentence:

To facilitate propagation of diagnostic information contained in NaNs, as much of that information as possible should be preserved in NaN results of operations.

This means the official suggestion in the floating point standard is to leave a qNaN exactly as you found it, in case someone is using it propagate “diagnostic information” using that payload we saw above. Is this an invitation to jerryrig extra information into NaNs? You bet it is!

What can we do with the payload?

This is really the question I’m interested in; or, rather, the slight refinement: what have people done with the payload?

The most satisfying answer that I found to this question is, people have used the NaN payload to pass around data & type information in dynamically typed languages, including implementations in Lua and Javascript. Why dynamically typed languages? Because if your language is dynamically typed, then the type of a variable can change at runtime, which means you absolutely must also pass around some type information; the NaN payload is an opportunity to store both that type information and the actual value. We’ll take a look at one of these implementations in detail in just a moment.

I tried to track down other uses but didn’t find much else; this textbook has some suggestions (page 86):

One possibility might be to use NaNs as symbols in a symbolic expression parser. Another would be to use NaNs as missing data values and the payload to indicate a source for the missing data or its class.

The author probably had something specific in mind, but I couldn’t track down any implementations which used NaN payloads for symbols or a source indication for missing data. If anyone knows of other uses of the NaN payload in the wild, I’d love to hear about them!

Okay, let’s look at how JavaScriptCore uses the payload to store type information:

Payload in Practice! A look at JavaScriptCore

We’re going to look at an implementation of a technique called NaN-boxing. Under NaN-boxing, all values in the language & their type tags are represented in 64 bits! Valid double-precision floats are left to their IEEE 754 representations, but all of that leftover space in the payload of NaNs is used to store every other value in the language, as well as a tag to signify what the type of the payload is. It’s like instead of saying “not a number” we’re saying “not a double precision float”, but rather a “<some other type>”.

We’re going to look at how JavaScriptCore (JSC) uses NaN-boxing, but JSC isn’t the only real-world industry-grade implementation that stores other types in NaNs. For example, Mozilla’s SpiderMonkey JavaScript implementation also uses NaN-boxing (which they call nun-boxing & pun-boxing), as does LuaJIT, which they call NaN-tagging. The reason I want to look at JSC’s code is it has a really great comment explaining their implementation.

JSC is the JavaScript implementation that powers WebKit, which runs Safari and Adobe’s Creative Suite. As far as I can tell, the code we’re going to look at is actually currently being used in Safari- as of March 2018, the file had last been modified 18 days ago.

NaN-Boxing explained in a comment

Here is the file we’re going to look at. The way NaN-boxing works is when you have non-float datatypes (pointers, integers, booleans) you store them in the payload, and use the top bits to encode the type of the payload. In the case of double-precision floats, we have 51 bits of payload which means we can store anything that fits in those 51 bits. Notably we can store 32 bit integers, and 48 bit pointers (the current x86-64 pointer bit-width). This means that we can store every value in the language in 64 bits.

Sidenote: according to the ECMAScript standard, JavaScript doesn’t have a primitive integer datatype- it’s all double-precision floats. So why would a JS implementation want to represent integers? One good reason is integer operations are so much faster in hardware, and many of the numeric values used in programs really are ints. A notable example is an index variable in a for-loop which walks over an array. Also according to the ECMAScript spec, arrays can only have 2^32 elements so it is actually safe to store array index variables as 32-bit ints in NaN payloads.

The encoding they use is:

* The top 16-bits denote the type of the encoded JSValue: * * Pointer { 0000:PPPP:PPPP:PPPP * / 0001:****:****:**** * Double { ... * \ FFFE:****:****:**** * Integer { FFFF:0000:IIII:IIII * * The scheme we have implemented encodes double precision values by performing a * 64-bit integer addition of the value 2^48 to the number. After this manipulation * no encoded double-precision value will begin with the pattern 0x0000 or 0xFFFF. * Values must be decoded by reversing this operation before subsequent floating point * operations may be peformed.

So this comment explains that different value ranges are used to represent different types of objects. But notice that these bit-ranges don’t match those defined in IEEE-754; for instance, in the standard for double precision values:

a valid qNaN:

1 sign bit | 11 exponent bits | 52 mantissa bits

1 | 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 1 + {51 bits of payload}

chunked into bytes this is:

1 1 1 1 | 1 1 1 1 | 1 1 1 1 | 1 + {51 bits of payload}

which represents all the bit patterns in the range:

0x F F F F ...

to

0x F F F 8 ...

This means that according to the standard, the bit-ranges usually represented by valid doubles vs. qNaNs are:

/ 0000:****:****:****

Double { ...

\ FFF7:****:****:****

/ FFF8:****:****:****

qNaN { ...

\ FFFF:****:****:****

So what the comment in the code is showing us is that the ranges they’re representing are shifted from what’s defined in the standard. The reason they’re doing this is to favor pointers: because pointers occupy the range with the top two bytes zeroed, you can manipulate pointers without applying a mask. The effect is that pointers aren’t “boxed”, while all other values are. This choice to favor pointers isn’t obvious; the SpiderMonkey implementation doesn’t shift the range, thus favoring doubles.

Okay, so I think the easiest way to see what’s up with this range shifting business is by looking at the mask lower down in that file:

// This value is 2^48, used to encode doubles such that the encoded value will begin // with a 16-bit pattern within the range 0x0001..0xFFFE. #define DoubleEncodeOffset 0x1000000000000ll

This offset is used in the asDouble() function:

inline double JSValue::asDouble() const { ASSERT(isDouble()); return reinterpretInt64ToDouble(u.asInt64 - DoubleEncodeOffset); }

This shifts the encoded double into the normal range of bit patterns defined by the standard. Conversely, the asCell() function (I believe in JSC “cells” and “pointers” are roughly interchangeable terms) can just grab the pointer directly without shifting:

ALWAYS_INLINE JSCell* JSValue::asCell() const { ASSERT(isCell()); return u.ptr; }

Cool. That’s actually basically it. Below I’ll mention a few more fun tidbits from the JSC implementation, but this is really the heart of the NaN-boxing implementation.

What about all the other values?

The part of the comment that said that if the top two bytes are 0, then the payload is a pointer was lying. Or, okay, over-simplified. JSC reserves specific, invalid, pointer values to denote immediates required by the ECMAScript standard: boolean, undefined & null:

* False: 0x06 * True: 0x07 * Undefined: 0x0a * Null: 0x02

These all have the second bit set to make it easy to test whether the value is any of these immediates.

They also represent 2 immediates not required by the standard: ValueEmpty at 0x00, which are used to represent holes in arrays, & ValueDeleted at 0x04, which are used to mark deleted values.

And finally, they also represent pointers into Wasm at 0x03.

So, putting it all together, a complete picture of the bit pattern encodings in JSC is:

* ValEmpty { 0000:0000:0000:0000 * Null { 0000:0000:0000:0002 * Wasm { 0000:0000:0000:0003 * ValDeltd { 0000:0000:0000:0004 * False { 0000:0000:0000:0006 * True { 0000:0000:0000:0007 * Undefined { 0000:0000:0000:000a * Pointer { 0000:PPPP:PPPP:PPPP * / 0001:****:****:**** * Double { ... * \ FFFE:****:****:**** * Integer { FFFF:0000:IIII:IIII

Take-Aways

- The floating point spec leaves a lot of room for NaN payloads. It does this intentionally.

- What are these payloads used for in real life? Mostly, I don’t know what they’re used for. If you know of other real world uses, I’d love to hear from you.

- One use is NaN-boxing, which is where you stick all the other non-floating point values in a language + their type information into the payload of NaNs. It’s a beautiful hack.

Appendix: to NaNbox or not to NaNbox

Looking at this implementation begs the question, is NaN-boxing a good idea or a bizzaro hack? As someone who isn’t implementing or maintaining a dynamically typed language, I’m not well-posed to answer that question. There are a lot of different approaches which surely all have nuanced tradeoffs that show up depending on the use-cases of your language. With that caveat, here’s a rough sketch of what some pros & cons are. Pros: saves memory, all values fit in registers, bit masks are fast to apply; Cons: have to box & unbox almost all values, implementation becomes harder, and validation bugs can be serious security vulnerabilities.

For a better discussion of NaN-boxing tradeoffs from someone who does implement & maintain a dynamically typed language check out this article.

Apart from performance, there is this writeup and this other writeup of vulnerabilities discovered in JSC. Whether these vulnerabilities would have been preventable if JSC had used a different approach for storing type information is a moot point, but there is at least one vulnerability that seems like it would have been prevented:

This way we control all 8 bytes of the structure, but there are other limitations (Some floating-point normalization crap does not allow for truly arbitrary values to be written. Otherwise, you would be able to craft a CellTag and set pointer to an arbitrary value, that would be horrible. Interestingly, before it did allow that, which is what the very first Vita WebKit exploit used! CVE-2010-1807).

If you want to know way more about JSC’s memory model there is also this very in depth article.